By Darren Johnson

Campus News

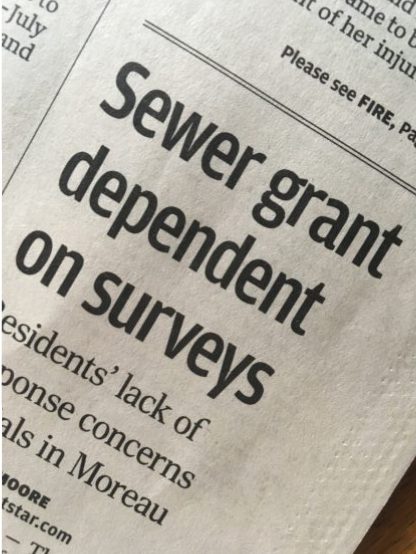

The story pictured above is an endangered species. It appeared on the bottom of the cover of the daily paper I received at my home yesterday, delivered by an adult in his car who only makes about $100 a week doing this, published by a company a county away, who outsources their printing to another county, as the print readership dwindles here and everywhere.

Wikipedia says this paper has a circulation of under 18,000, so a story about a sewer district in one of the dozens of small towns in its jurisdiction surely won't get a lot of views. In the story even, sewer officials lament that they can't get enough interest in a survey they are conducting about the sewers. At least that's what I think it says. I only read the headline and lead, determined I don't have any interest in this sewer district in a faraway town, and didn't jump to page 6.

My guess would be only a handful of those 18,000 potential pairs of eyeballs jumped to page 6. Maybe they live in the town with the sewer issues. Maybe they are just the anal-retentive types with lots of free time who insist on reading every word in the paper. The online version of this story probably isn't tearing up the Internet, either. If it gets 100 views online -- which seems optimistic -- that means the paper will only make 20 or 30 cents -- not dollars, cents -- on that story with the banner ads that accompany it, that pay via impressions.

It's hard to pay a reporter who may make $40,000 a year or more with pennies. I wrote such stories when I was a community journalist. Before newspapers decided to give everything away for free online, we wrote these beat stories as an obligation. We had no clue how many people read such dry, hyper-local stories, but we were on the ground, and personally knew the people we covered at each beat, and felt a duty to tell their story. At least we knew they read the stories, because they'd comment about them when we'd see them in person -- and they'd call in angrily if they felt misquoted. I don't recall ever wondering if 10 people would read my story or 100 or 1000.

The problem now is, with digital analytics, we know such stories get tumbleweeds. And while the print model of the paper relied on overall readership -- not the readership of one particular story -- the online versions of papers are much more specific. Few people are Googling about this sewer district, few people are commenting on it on message boards, it doesn't have a sexy picture to go with the story. So, again, pennies.

As newspapers give up on their print editions and move to the web, will these little stories get left behind? Probably, because they just don't have a sustainable business model backing them. And what will be lost? A new study suggests that reduced press coverage results in less watchdogging and thus more government corruption and/or ineptness, and thus higher taxes.

And think about all the little newspapers with their little stories closing everywhere, abandoning their beats, and then what will happen? Will politicians take citizen journalists who complain about their local issues on Facebook as seriously as they took a printed newspaper written by trained journalists? Doubtful. Mark Twain warned, to paraphrase, "Never pick a fight with people who buy ink by the barrel and paper by the ton." There is no equivalent of that on the web. There may never be.

So perhaps this is an obituary for all the little stories that may not mean much individually, but, collectively, they keep thousands of local governments on their toes, and make them better. We taxpayers save millions thanks to such diligence.

Or perhaps we'll be able to come up with a business model that can adequately feed these watchdogs with journalism degrees -- so that they can continue to protect us.

Darren Johnson has practiced and taught journalism and owns Campus News, a newspaper that's actually growing. To learn how to save your newspaper, contact him at editor@cccn.us.

Facebook Comments