Scientists at The City University of New York are hard at work this summer on a range of research projects that could lead to important advances in the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic locally and globally.

The research includes an ongoing project at Queens College to monitor the level of coronavirus in New York City sewage to assess its true prevalence, help identify new outbreaks before testing does and guide health officials’ response. Another study aims to discover how the virus spreads within an indoor environment like a classroom, and what interventions might work best. At CUNY’s Advanced Science Research Center, a team is developing biological sensing technologies that could detect the presence of coronaviruses on surfaces and prevent them from surviving. And a forensic and biological anthropologist at John Jay College is studying bats in hopes of helping locate targets for potential immunization and drugs for humans.

“CUNY’s research mission has long been sharply focused on science in the public interest and discovery with real-world benefit. No area is more deserving of our researchers’ attention right now than the coronavirus pandemic,” said Chancellor Félix V. Matos Rodríguez. “We are proud of our faculty who are rising to the occasion, earning grants, forging partnerships and in some cases repurposing their work to jump on research that can make a real difference in this public health crisis.”

Several of the projects being undertaken by CUNY researchers are supported by Rapid Response Research (RAPID) grants from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and some involve impromptu collaborations with research universities in New York and around the country.

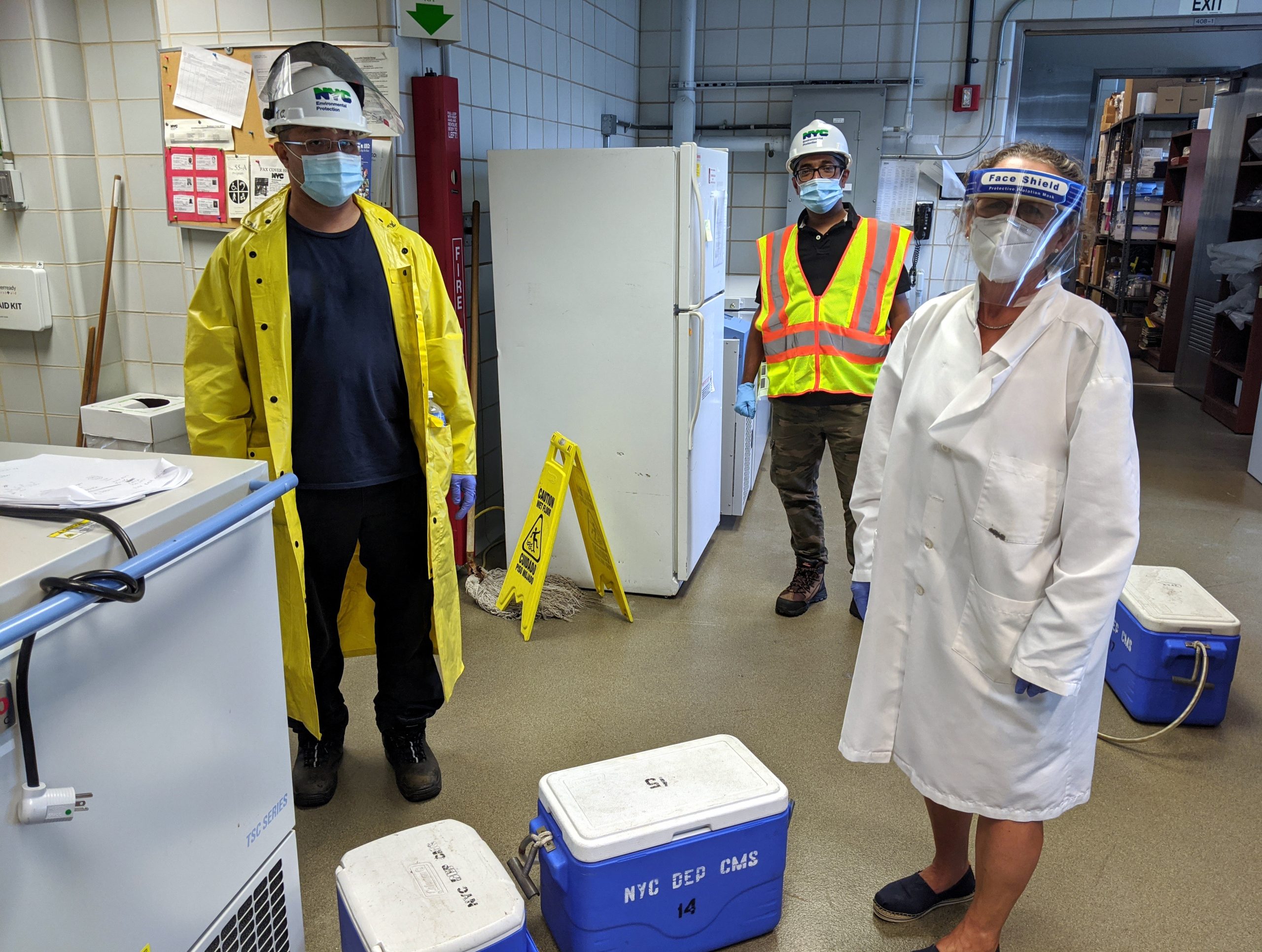

Since May, John Dennehy, a professor of biology at Queens College who studies viruses, virus ecology and evolution, has received and tested weekly samples from each of New York City’s 14 wastewater treatment plants in an effort by the city to assess the presence of COVID-19 more accurately than it does from testing and clinical data.

“Sampling the sewage is better than relying on testing and diagnosis because there are many people walking around who are asymptomatic, don’t know they are infected and aren’t getting tested,” said Dennehy, who is working with Monica Trujillo, an associate professor in the Biological Sciences and Geology department of Queensborough Community College.

With funding from the city’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), Dennehy’s lab developed a protocol for measuring the concentration of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and extrapolating how pervasive the disease is in the communities that feed each wastewater plant. The city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene can use the results in its efforts to monitor the virus both in individual communities and citywide. “It can help them determine if more resources should be allocated to a particular area,” Dennehy said. “And when the virus starts to go away, we hope, we can monitor it to see if it’s coming back.”

Another aspect of Dennehy’s research is to use the wastewater samples to genetically sequence the COVID-19 virus in order to assess whether it is mutating.

“Current efforts to characterize the genome of circulating coronavirus are biased toward genomes obtained from critically ill patients,” said Dennehy. “But if you want to test whether the virus is evolving and you’re only sampling from people who are hospitalized, you’re not getting the full breadth of the virus. The genetic diversity of coronavirus in the wastewater gives you an unbiased and much more meaningful sample of a population.”

The testing is being conducted in Dennehy’s lab at Queens College, but he and his colleagues are training DEP staff to eventually take over what the department is calling “the CUNY protocol” at its lab in Newtown Creek, Queens. Meanwhile, Dennehy and the CUNY protocol are part of a nationwide collaboration among 30 laboratories to improve the reliability of sewage testing and make it a major tool in the battle against the coronavirus.

“Almost every major city is now doing some sort of wastewater program and we’re coordinating to determine which method of testing best detects coronavirus,” said Dennehy.

Here is a look at some other coronavirus-related research being conducted by CUNY faculty:

· Dennehy is conducting another research project to model the way COVID-19 spreads in indoor environments and test the effectiveness of various cleaning, spacing and ventilation interventions. With a RAPID grant from the NSF, Dennehy is working with colleagues at The New School to simulate the coronavirus’s behavior in a classroom by infecting the air and surfaces with a virus that’s biologically similar to the COVID-19 virus but harmless. They will try to produce a model that can predict how the virus spreads from an infected person in that environment, what happens when it reaches others and which strategies may best impede infection. “We jumped into this coronavirus situation with very little understanding of how viruses actually get spread,” said Dennehy. “There have been so many mixed messages about stopping the spread over the past five or six months but with very little empirical data.”

· Rein V. Ulijn, director of the Center for Advanced Technologies in Sensors at CUNY’s Advanced Science Research Center, has been working with colleagues around CUNY to kick-start projects that could help curtail the spread of coronavirus and play a role in the city’s efforts to reopen safely. Two of the projects are focused on biological sensing technologies that are being repurposed from cancer to coronavirus detection and the development of smart surface coatings that prevent viruses from sticking and surviving. Ulijn’s own research lab is also looking at ways of rethinking personal protective equipment materials in anticipation of a major waste problem triggered by the increased use of plastic materials by medical workers. “After the crisis hit, my colleagues and I thought about what we could do to help and repurpose research for COVID-19,” said Ulijn. “We’re focused both on contributing to solving the current crisis and developing or accelerating technology to address the needs of New York post-COVID.”

· At John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Angelique Corthals, a biomedical researcher and forensic anthropologist, is at work on two research projects involving bats, the suspected source of the coronavirus, funded by NSF COVID RAPID grants. One project, a collaboration with researchers at Texas Tech University, looks at the immune systems of the species of bat most likely to carry coronaviruses and how their immune genes allow them to be resistant or tolerant to viruses. The project’s ultimate goal is to identify specific proteins or genes as targets for potential medicines and immunizations for humans. A second project, with colleagues at Stony Brook University, will look at the differences in the epithelium —the lining of the respiratory tract— of bats, humans and mice to understand how it may play a role in bats’ resistance to coronaviruses. Corthals is being assisted in her research by her John Jay undergraduate students. “What really excites me,” said Corthals, “is the possibility that, through our work, we could be able to predict or prevent another pandemic, or at least mitigate a pandemic, because we will know where to look before it spreads to a human population.”

Facebook Comments