By Dave Paone

Campus News

In the 1976 feature film Rocky, the movie’s namesake explains to his date, Adrian, how his father steered him to a career in boxing when he was 15.

“He says to me, ′You weren’t born with much of a brain, so you better start using your body.′”

The introverted and awkward Adrian replies, “My mother, she said the opposite thing. She said, ′You weren’t born with much of a body so you better develop your brain.′”

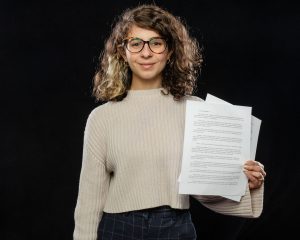

In an example of life imitating art, 23-year-old Carmen Saffioti of East Meadow, Long Island, had a similar experience.

At seven years old, she had taken her first gymnastics class and was the only one who couldn’t do a handstand. Her mother said to her, “You are unathletic.”

For the 13 years that followed, Saffioti believed this statement to be a fact, and much like Adrian, spent her time developing her brain.

“I became very into excelling at school and doing other activities that didn’t involve exercise whatsoever,” Saffioti told Campus News. She even held prejudice against those who pursued physical endeavors, believing, “Anything using your body was kind of inferior to what you could do with your brain.”

That all changed during the lockdown of 2020.

At the time, Saffioti was an undergrad student at Brooklyn College with a major in journalism and media studies and a minor in marketing. She was in her bedroom one night scrolling through TikTok, when she came across a video of someone showing off her roller skating skills.

As crazy as it may sound, this one video by a complete stranger changed Saffioti’s life. “I was just very in awe of it,” she said.

Saffioti was hit by the thunderbolt of inspiration and soon after dusted off her barely-used roller skates from when she was 10 and gave them a try. (They were adjustable, so she still fit in them.)

Her first time back on skates was a disaster but Saffioti was determined. It took a lot of practice, but eventually she became proficient, and for the first time in her life actually enjoyed physical activity.

Prior to this, Saffioti’s eating habits were poor. She barely ate during the day and when she did, it was usually one meal and some snacks, making her underweight and undernourished.

Her newfound love of athletics helped her change her eating habits for the better.

Many people found the lockdown a very depressing time. The populace was isolated from each other and humans, being social creatures, found this isolation dialed up their depression. This included Saffioti.

Skating fixed that, too. She purchased new skates and with a lot of time on her hands, would go to the tennis courts near her house and practice for hours. She feels by exercising regularly she’s emotionally, mentally and physically restored.

However, there’s an element of danger to roller skating. “I broke my wrist last year in December,” Saffioti said. It was the one time she didn’t wear her wrist guard. “The day after I got my cast taken off, I was back in the skatepark.”

Saffioti wanted to share her new love with her friends, but none were interested in participating. So that meant she needed to find some new ones who shared her interest.

That wound up being the Long Island Roller Rebels, which is a professional roller derby team. “I basically joined just to meet other people who love to skate like I did,” she said.

Roller derby players go by stage names, and they’re usually both comical and threatening. On game days, Saffioti goes by “Panera Dread.”

Panera Dread had her first roller derby meet last year and the Roller Rebels lost, but she won “MVP Jammer” (as voted by the opposing team) and has the trophy to prove it.

Moxi Skates is a company that sells recreational roller skates and related equipment. Each year they hold an essay-writing contest and the winners get to attend their roller-skating camps in California or Pennsylvania for three days in the spring for free.

It’s there that students learn how to perform intricate tricks and dance moves at a skatepark. Since the instructors are professional skaters, the cost for the week is $499 plus a $20 booking fee.

Saffioti put her journalism education to good use and wrote up her story and was one of 20 winners from 160 entrants this year.

“Overall, I found Carmen’s essay to be really inspiring and highly authentic,” Brian Andrews, one of the judges and director of operations at Moxi, told Campus News in an email.

“Reading the essay felt like hearing someone talk, just very natural and from the heart. A story of triumph over fear and adversity.”

Saffioti earned her BA in 2021 and is currently a grad student at Baruch College as a digital marking major.

She has never seen the original “Rocky.” “I’ve seen the third one,” Saffioti confessed. Nevertheless, she’s taken the advice from Rocky’s father and Adrian’s mother, and has developed both her brain and her body, which together have strengthened her emotionally and mentally.

If Rocky and Adrian were to know, they’d call her a winner.

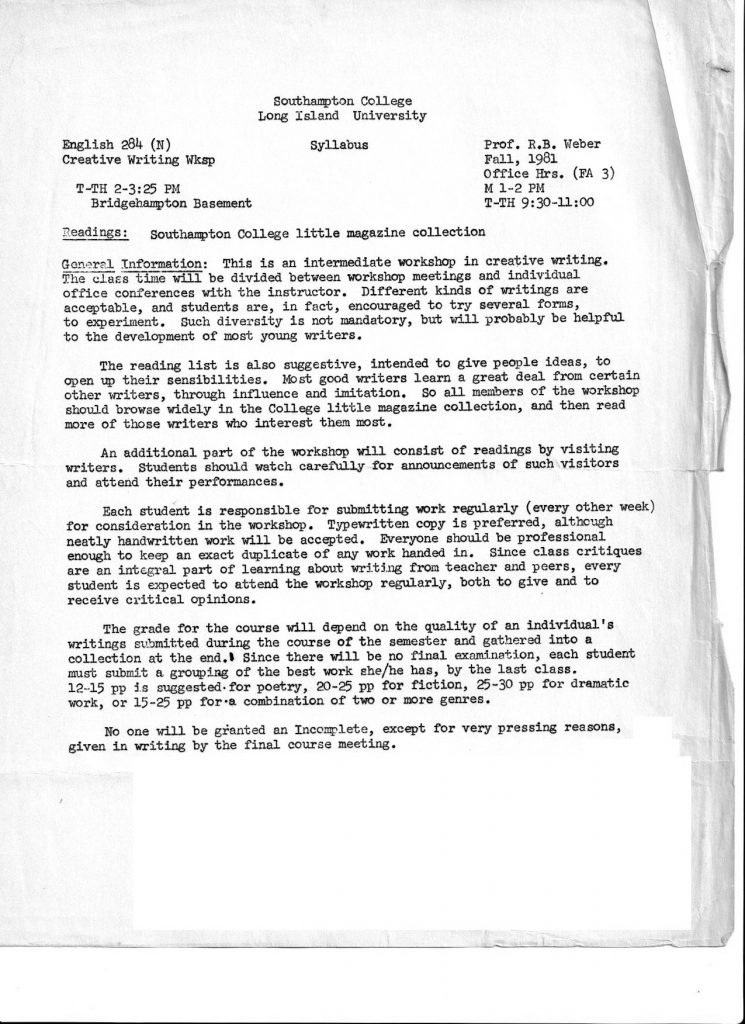

Carmen Saffioti’s Winning Essay

“You are unathletic. “

This sentence, like a mantra, was said over and over again throughout my childhood and into adulthood. It was first said to me by my mother, after my first gymnastics class, when I was the only one who couldn’t do a handstand.

To her credit, my mom didn’t repeat this sentence nearly as often as I did to myself. I held it in my mind and treated it like a prophecy any time I saw someone complete an athletic feat. It comforted me. I reminded myself that I was simply incapable of even trying due to my intrinsic lack of athletic ability.

Soon after my first gymnastics class, I accepted this truth and gave up. I vowed to never try another sport again. As I got older, I cringed at the idea of exercise. I walked during “the mile” in gym class.

I began to view my physical body as simply a vessel. Actually, I really felt like it was a cage for my mind and soul. I wanted to be free of it so I ignored its needs, and desire to move. I hoped that if I ignored my body, others would too, and I could escape its clumsy “unathletic” confines.

That is, until I discovered roller skating, and discovered what my “well-being” means.

During the pandemic, sitting in my dark bedroom, I scrolled through TikTok. In this familiar setting for me at the time, I came across a video of a gorgeous person roller skating backwards flawlessly through a city plaza. I stopped and paused, watched the video about six more times. And then, I kept on scrolling until I got bored and closed the app.

I saw a lot of cool athletic things on TikTok: people doing back flips or dancing in seemingly impossible ways. I dismissed them, as I always had; I told myself, “I’m just not athletic” and moved on.

But this time was a little different. I kept thinking about the video, and how the person I saw looked so free. So, I dug out my old rollerblades that I used about twice when I was 10 years old. I strapped them on and fell. Immediately. But for some reason, that didn’t stop me. I wanted to be free, like that roller-skater.

I discovered something I had never realized before: if I kept trying, I kept getting better. I outgrew my cheap roller blades pretty quickly, and I got my first pair of roller skates.

I still couldn’t explain my desire to roller skate. But I felt more energetic. I slept better at night, and I felt less depressed and anxious. All of these are the benefits of exercise. But I didn’t even realize I was exercising at the time, I thought I was having way too much fun!

I finally started to connect my mind and my soul to my body. As my twiggy legs started to grow muscles, I started to feel the desire to eat more than once per day. I wanted to care for my body, rather than just ignore it. Because once I began to care for my body, I wanted to push my body to its limits, and to see what it could do.

The first time I went to the skatepark, I was terrified. I would look at ramps, banks, ledges and a-frames and constantly thought to myself: “I could never do that!” Of course, the self-doubt did not just go away. Although I was improving at roller skating, I still felt weak and unathletic. I felt a sort of imposter syndrome, like I accidentally learned transitions, backwards skating, heel toe spins, and toe spins.

Despite this, I pushed myself to try at the skatepark. When I got my first stall, drop in, 180, 360, cartwheel, etc. my jaw dropped every time. My body was doing things I never thought it could do. I began to understand (as strange as it sounds) that my body was a part of me. I listened to it, I understood it, and I loved it. That is how roller skating improved my wellbeing.

I didn’t realize, I wasn’t, nor could I be well unless I began to care for myself emotionally, mentally, and physically. For so long I ignored the physical. I was underweight and malnourished. I was neglecting my physical self.

When I had finally embraced my athletic abilities, it felt like a whole new world had opened up. Not just in roller skating, but with exercise and other activities as well.

Today, 3 years later, I love going hiking, I regularly go to my college’s gym, and I have joined a roller-derby team! All because one day I saw a TikTok of a roller-skater, and thought “I can try that” instead of “I could never do that.” My confidence has exploded, and I can’t wait to take the next challenge.

Thank you Moxi!

Facebook Comments