By Adashima Oyo

and Silvia Rivera Alfaro

Special to Campus News

In our years of teaching undergraduate students at City University of New York (CUNY) colleges while being Ph.D. students ourselves, it is abundantly clear that academia should reassess its need and dependence on grades. While most students aspire to get an “A” at the start of the semester, what do grades really measure and do we really need them? We argue that the use of grades presents more harm than benefits for college students, professors, higher education, and the pursuit of learning and knowledge.

In our experience as students and instructors, one problem is that grades focus on the result instead of the learning process. Furthermore, grades produce anxiety and can make it harder for everyone, but especially harm students with neurodiversity who might be triggered by the grading process or students who have diagnosed or undiagnosed learning disorders.

Do grades really mean what we think they mean? Sure, on the surface college students have been conditioned to believe that an A represents “excellent,” and many have been conditioned to assume that a student with a 4.0 GPA must be “smart.” In fact, from a fairly young age, as soon as one enters elementary school in some instances, students are presented with an overemphasis on grades. While grading is standard practice in most classrooms from kindergarten to college, an overdependence on grades presents many problems for students and teachers, especially college professors.

The recent trend of college students resorting to ChatGPT to write their papers sent shockwaves across college campuses. However, it also highlighted the need for college professors to revisit the value of grades and to rethink their pedagogy, or teaching, practices. After all, what are grades actually measuring? Surely, it’s not always intelligence. Depending upon the discipline or subject matter, it could be that an A grade simply represents a student who was able to follow directions or regurgitate and recycle what a professor said instead of sharing their own ideas, even if those ideas are imperfect. However, across many college campuses, students are overly focused on their GPAs and meeting the expectations outlined on the syllabus by their professors.

While most students do not want an F on their transcripts, failure is an important part of learning. If professors instead focused on learning outcomes that are not tied to a letter or numeric grade, the classroom might be more focused on student-driven learning and cooperative learning instead of a competitive and individualistic environment. In other words, if we want to create safe spaces for learning, we need to have spaces where failure is part of the process, but grading goes in the opposite direction: It punishes failure. Further, given the large body of research that indicates grades are sometimes subjective and misleading, or that professors make mistakes with grades, it is time that higher education reimagine grading. This does not mean that students do not require assessments.

If the grades are not really an element of pedagogy benefiting the students, it’s natural to wonder “For whom do grades measure?” They respond to a model of education that was created to train workers after the Industrial Revolution, where each cohort goes through the assembly line. In that logic, grades are like quality control checking the students as a manufactured product. At the same time, the grades help the supervisor to see how the worker training those students is doing their part in the production line. Grades, thus, are for a system where education is an enterprise, and values such as innovation and creativity are on the side.

The use of grades also presents problems for adjunct professors. Grading requires a lot of time on the instructors’ part (to prepare grades that will be forgotten) when the time could be used for more meaningful learning. Given that it’s not unusual for adjuncts to teach large sections of classes, many struggle with the need to keep up with grading demands from program chairs and their students. Although it may be easier to rely on using quick letter grades or Scantron exams with multiple choice and true/false options to assess students, the results of those assessments may not be a true reflection of the learning that has or has not taken place in the classroom.

In short, for all participants, grades focus on the product, not on the process. Students, faculty, and everyone who participates in the learning process should be free to focus on the process and innovate with new pedagogies that bring the best to the present of humanity.

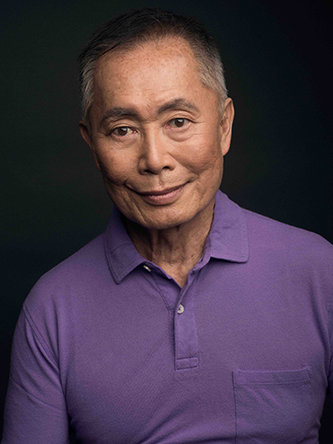

Adashima Oyo (left) is Executive Director of the Futures Initiative at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is a recent graduate of the Ph.D. Program in Social Welfare at the Graduate Center and an Adjunct Professor at Brooklyn College and NYU.

Adashima Oyo (left) is Executive Director of the Futures Initiative at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is a recent graduate of the Ph.D. Program in Social Welfare at the Graduate Center and an Adjunct Professor at Brooklyn College and NYU.

Silvia Rivera Alfaro (right) is a Fellow-in-Residence at the Futures Initiative and Digital Fellow at GC Digital Initiatives at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is currently a student in the Ph.D. Program in Latin American, Iberian, and Latino Cultures at the Graduate Center.

Facebook Comments