By Dave Paone

Campus News

Paula Wunder used to be in daily contact with convicted murderers, armed robbers and active members of the Crips and the Bloods. She didn't work in the court system; she worked as a secretary/teacher's aide in Second Opportunity School in the Bronx.

To make her story even crazier, all these felons were in seventh and eighth grades.

One day a new girl arrived and said to Paula, "You know what I'm in here for?!" Paula showed her the folder with her name on it and said she did. The girl went on to brag about how she and another girl had a fight on the roof of a building and then proudly exclaimed, "I came down by the stairs — she didn't!"

The new girl was in seventh grade.

Paula's birth in 1955 put her at the tail end of the hippie era by the time she was in her teens. She attended Woodstock, the be-all-end-all hippie event, in 1969 at age 14.

While she hung out with her older sister (a "definite, definite hippie,") on West 4th Street in Greenwich Village (historically a Bohemian stomping ground), she wasn't in it for the long run.

"Although it was very interesting, it really wasn't me," she said. "I needed a firm foot on the ground in my parents' kind of society while I dabbled with all these other lifestyles."

The public school system not only provided a grounded career but also provided summers days off (to comb the beach), which was a major factor in pursuing one.

Paula received her AA from Kingsborough Community College, which included a "strict course of secretarial sciences" that helped her land a job as a secretary at an NYC public school district office in East New York, Brooklyn.

East New York was (and is) a rough neighborhood. But the way the system worked at the time was the rookies started out in such places so Paula didn't have a choice.

She spent the rest of her career working in crime-ridden sections of New York City. (The schools had a "battery fund" to replace the stolen batteries from employees' cars; they were stolen that often.) Her "official" jobs were some sort of secretarial position, but since these places were always understaffed, she actually worked as a teacher's aide more often than not.

It was when the Board of Education started the Second Opportunity Schools program that Paula found her niche. This is where students who were either convicted of felonies and awaiting sentencing, or were charged with felonies and awaiting trial, attended school. Middle school.

She found being an additional authority figure in the classroom, but with "a more personal presence," helped keep the troublemakers in check.

Paula essentially took on the duties of a social worker, but said, "I did way more than a social worker ever did. I got involved in all the kids' lives, in a whole different way."

While on paper she was a school secretary, in reality she performed tasks such as picking the glass out of students' heads when they were thrown through a window by other students.

She actually treated them as if they were her own children, putting her arm around them and giving them a kiss on the forehead when they did something good.

Her desire to help these kids went beyond the walls of the school. This included giving them food to make meals at home and taking them roller skating and horseback riding, often paying for everything herself.

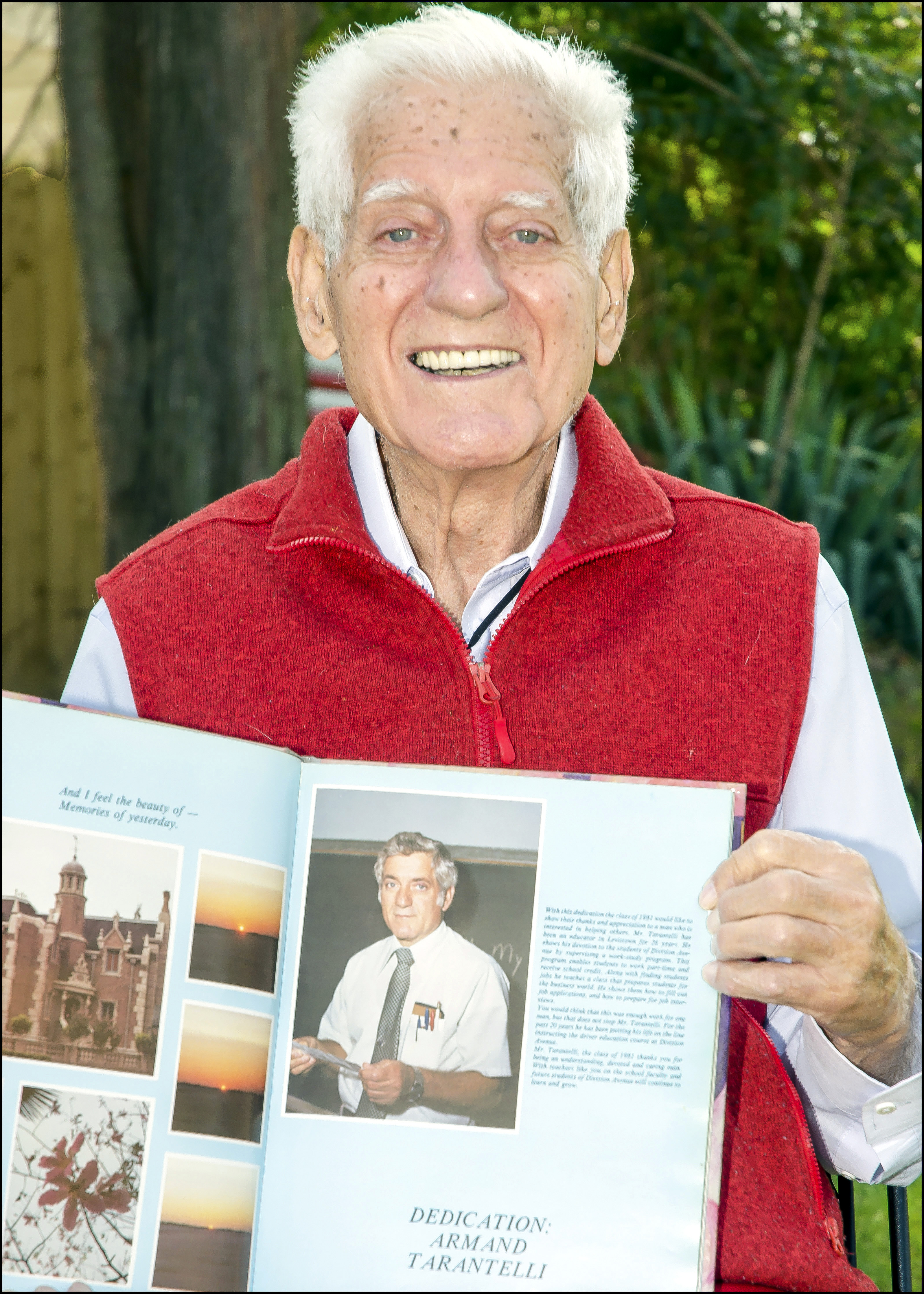

Armand Tarantelli (pictured) has a similar story. After serving in the Army during World War II, he attended the School of Education at New York University on the G.I. Bill. (The G.I. Bill was paid college tuition to veterans as additional compensation for fighting in the war. Seven point eight million veterans went to college or trade school on Uncle Sam's dime.)

Armand had learned cabinetmaking while attending a vocational high school, so it was a logical decision to become a shop teacher.

For decades American high schools had an "industrial arts" curriculum, which included classes in anything from auto repair to woodworking to metalworking. Industrial arts was also known as "shop."

At many schools shop was a dumping ground for the less academic students. Guidance counselors, at a loss for electives for these students, would sign them up for shop.

Armand started at Division Avenue High School in Levittown, New York in 1953.

In his early days as a teacher, Armand didn't have an abundance of behavior problems in the classroom. He credits this to much of the faculty having been World War II veterans who were big on discipline.

According to Armand, no one wore shorts to school and the vice principal would actually suspend girls if their skirts were too short.

However, as the years went on, more and more students dropped out of high school nationwide. By the 1970s, the federal government decided to do something about it.

The answer was the School to Employment Program, or STEP. Armand, or "Mr. T." as he was affectionately called by his students, took on the job as the STEP coordinator. He was pretty much left alone to run the program as he saw fit.

The idea was to find these at-risk students part-time jobs where they'd work during the school day. They'd attend classes in the morning and then work a job off-campus for the remainder of the school day.

Mr. T.'s daughter, Claudia, says to this day she bumps into former students, who are now successful, who say they got their first job thanks to her father.

However, Mr. T. didn't think this was enough and went above and beyond for these kids. His plan was to get each of them into either college or a trade school.

He describes these kids as "hazards," and "incorrigible." "The teachers wanted them out," he said. "My biggest enemy was the teachers."

He contacted admissions counselors at colleges and BOCES on Long Island to see what it would take for these students to be accepted. He would often borrow the driver's ed car (Mr. T. was also the driver's ed teacher) in the morning to drop off a student at a college to observe the place and then pick him up in the afternoon.

Mr. T. ran this program for about 10 years, until the federal government terminated it. To the best of his memory (he's 95 this month), he believes 100% of the students he mentored were accepted to college or a trade school.

Mr. T. retired in 1982 and Paula in 2006. Times have changed enormously since then.

Industrial arts is just about extinct. (Sometimes middle schools have "technology" class, which is a mere shadow of what industrial arts was.) Guidance counselors use other electives as the dumping ground.

Teachers can no longer drive with students in their cars, even if it's the driver's ed car and they're going to see a college. Employees can no longer fraternize with students outside of school and the days of kissing them are definitely over.

Although the methods of Mr. T. and Paula were undeniably successful, they and their schools could be sued for such actions today, and they could actually be arrested for them as well.

"I think it is very important to work with high-risk students, especially in communities that need quality educators," said Michele de Goeas-Malone, the program director in LaGuardia Community College's education department.

"As educators, I believe that it's our job to make quality education accessible to all students. And I don't believe that means taking kids roller skating or horseback riding. It means investing time working with them on developing the competencies and skills they'll need to have to be successfully employed," she said.

For years Paula was fortunate enough to have administrators who supported her efforts. One principal was like a father to her. But near the end she not only lost her administration's support, they made her a target, and it was then she knew it was time to go.

Paula feels teachers today are walking on eggshells, constantly avoiding being brought up on charges or getting sued. "Now the welfare people have a new income," she said.

It makes one wonder why anyone would want to work with at-risk children at all these days. But as Paula simply puts it, "Somebody has to do it."

Dave Paone, who has been writing and photographing for Campus News for over 10 years, has won two journalism awards from the Press Club of Long Island and one from the New York Press Club. From the PCLI, he won second place in the Best Headline category from his story on a cat café and third place in the Entertainment category for his story on students who perform standup comedy. From the NYPC, he won in the Entertainment category for his coverage of the NYC Anime Convention. All three stories ran in Campus News last year, making them eligible for the PCLI’s 2020 Media Awards and the NYPC’s 2020 Journalism Awards.

Dave Paone, who has been writing and photographing for Campus News for over 10 years, has won two journalism awards from the Press Club of Long Island and one from the New York Press Club. From the PCLI, he won second place in the Best Headline category from his story on a cat café and third place in the Entertainment category for his story on students who perform standup comedy. From the NYPC, he won in the Entertainment category for his coverage of the NYC Anime Convention. All three stories ran in Campus News last year, making them eligible for the PCLI’s 2020 Media Awards and the NYPC’s 2020 Journalism Awards.

Bonus: The Comics (Click on Other Stories to See More Comics)

"Gasoline Alley" by Jim Scancarelli. In agreement with TCA. Click to Expand.

Facebook Comments