By Darren Johnson

Campus News

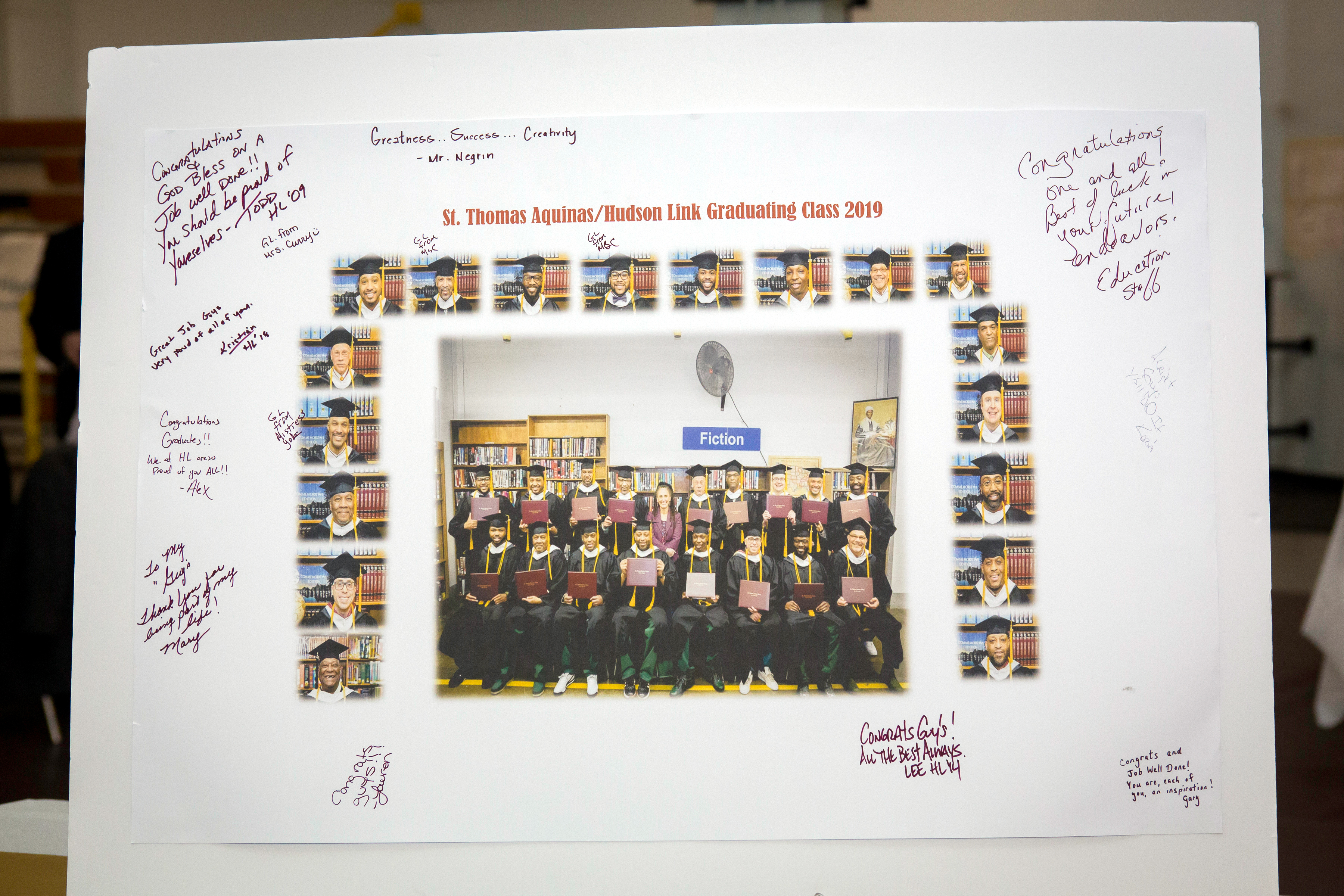

In a first-ever ceremony this past summer, 18 male inmates at Sullivan Correctional Facility received their B.S. degrees in Social Science through a brand-new program. And this fall a second cohort of 24 students has taken their place in the prison’s spartan classroom.

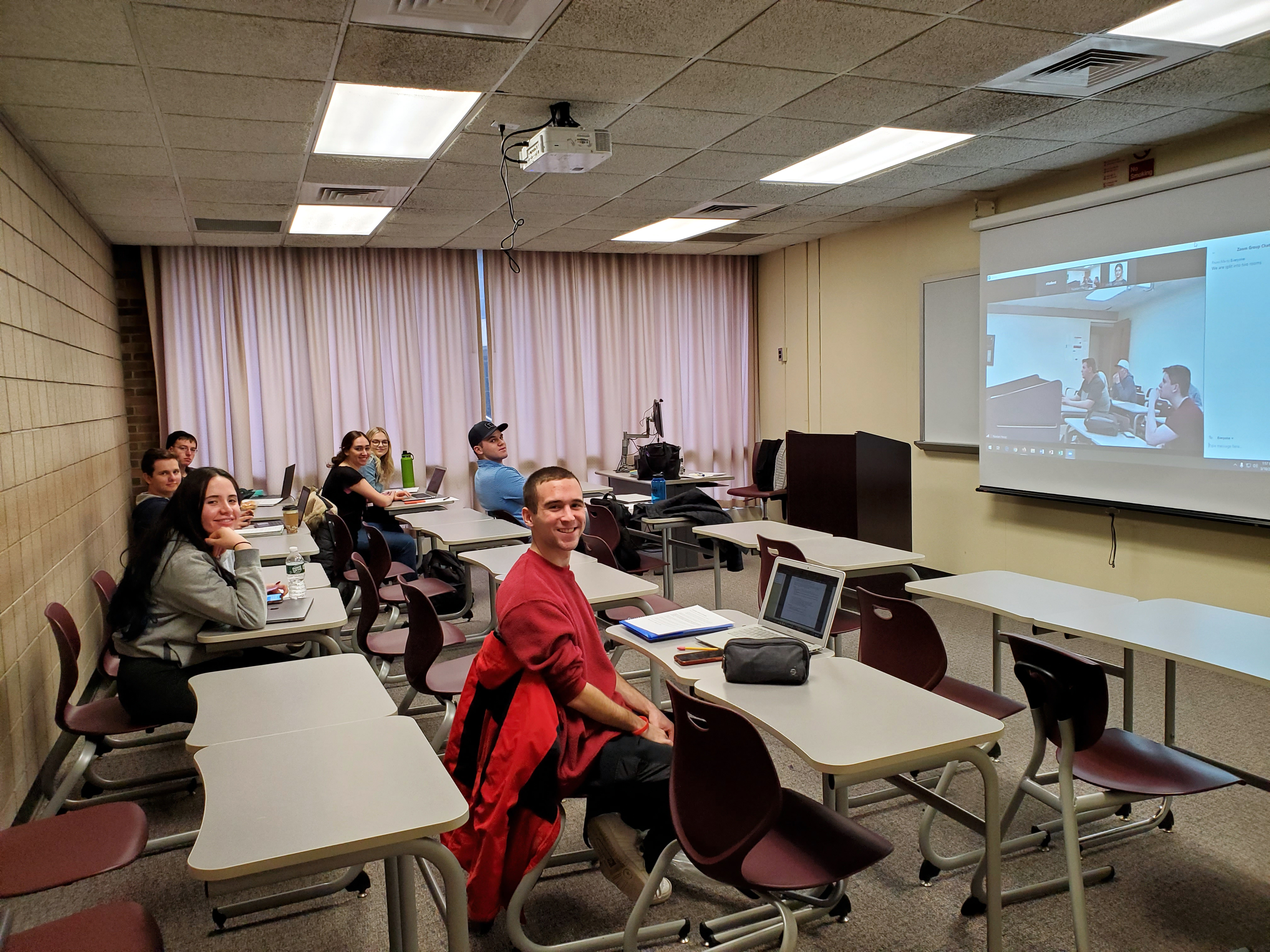

The typical age of the men is mid-40s. Their average stay in years is in the double digits. They aren’t allowed any technology. The professors can’t even use PowerPoint.

And, yet, the inmates are prospering, and the program is changing lives.

“The students’ level of preparation and their work – the students work at 110%,” said Dr. Stacy Kinlock Sewell, a professor of history from St. Thomas Aquinas College who teaches Colonial and Postcolonial Vietnam in the prison and also manages the college’s off-campus programs. “They’d all read the material before class, they’re thinking about it, they’re talking about it in the yard. …

“They asked questions and made me go deeper into the material.”

The program is funded through non-profit Hudson Link, which runs similar programs at other New York prisons, with the bachelor’s portion at Sullivan Correctional Facility taught by St. Thomas Aquinas College professors and the prerequisite associate’s in Liberal Arts and Humanities taught by SUNY Sullivan professors, with both degrees administered through their respective schools.

In total, 119 men are currently taking either associate’s- or bachelor’s-level courses at Sullivan Correctional Facility – a third of the prison’s population. A stringent vetting process finds the best students in the prison for the St. Thomas Aquinas College cohort.

Mary B. Donnolly, Academic Coordinator for Hudson Link, conducts interviews, helps evaluate math and essay application tests, and checks their behavioral records and how much time they have left on their sentence. If they haven’t had disciplinary issues in the past 18 months and have at least three years left in their sentence, they may qualify. Before committing funds, Hudson Link wants to ensure the inmates can practically complete the degree before their release date. And the results have been amazing. Donnolly said that the national recidivism rate for convicts is “sixty to seventy percent,” but for Hudson Link grads it’s “two percent.” She said this program changes inmate behavior, and gets them thinking in a different way.

“The fact that an outside person comes in and treats them with respect and expects them to do the work …. For a lot of these men, this is the first time that their families are telling them they are proud of them. And they have an opportunity to do the right thing. For some of them, they have been inside 15-20 years already. For them to be able to offer that to their families is such a gift,” Donnolly said.

Sewell said that teaching these classes is intense, as the students come in ready for deep discussions. And instructors can’t use any technology. Even a History of Jazz class was taught without any audio equipment.

Sewell said that teaching these classes is intense, as the students come in ready for deep discussions. And instructors can’t use any technology. Even a History of Jazz class was taught without any audio equipment.

“I’d come out of there exhausted,” Sewell said.

“They work so hard. They challenge one another. They are in friendly competition with one another. They riff off of one another,” she added. “One will say, ‘I’m going to get a 4.0, you’ll only get a 3.9.’”

“You know they will have done their reading, they will have completed their assignments and they will come to class.”

In many ways, she said, the prison, with its close confines and the frequent fraternizing of its students, allows for a unique learning environment that would be hard to replicate on St. Thomas Aquinas College’s campus. As well, because these students are older, and have obviously lived through difficult experiences, they have unique views. In Sewell’s Vietnam course, for example, some students were old enough to remember the issues of the Vietnam War, and, because of their experience in the U.S. penal system, can look at the governmental actions of that era with a more cynical eye than traditional students of today.

Dr. Ben Wagner, a psychology professor at St. Thomas Aquinas College, taught Psychology and the Law in the prison.

“When I’d teach my traditional students at STAC, these are 18-22 year olds, it just blows their minds. They’re like, ‘I can’t believe it’s like that!’” he said. “But when I’d bring it up in the prison, they’re like, ‘Yeah, that really happened to me.’ …

“Part of it is, they’re just adults. And adults in general are just more critical. But they also can come at an issue from a different perspective – often a radical perspective – which I don’t get from my traditional students, which can be nice to see.”

“Part of it is, they’re just adults. And adults in general are just more critical. But they also can come at an issue from a different perspective – often a radical perspective – which I don’t get from my traditional students, which can be nice to see.”

Wagner said he was really impressed with the quality of the cohort.

“It’s like teaching an honors course. Students came into the first class already with prepared questions. Before that, I’d never had a student read the book before the first class started.

“They care. They do the reading. They make connections to their other courses and their lives. They’re hungry to learn.

“They see each other out of class, and will already have had a critical discussion before each class begins.”

Neither professor said that safety was an issue.

“The No. 1 question people ask me when I tell them I’m doing this is, ‘Are you scared?’ And what you realize really quickly when you do this is these are people, just like any other people. You see their humanity, their fear, their excitement and their happiness and their sadness,” Wagner said.

“They are very serious students and they are very appreciative of what we are providing to them; and they are not intimidating at all.”

Donnolly said many former inmates who had received degrees through Hudson Link landed office jobs upon their release; some work for non-profits, helping other people avoid prison.

But sometimes outsiders will be cynical.

“I get it all the time. There are people who say, ‘Oh, I’ll just go and tell my son to go out and kill somebody and he’ll get a free education.’ And I have a standard reply. I say, yes, these men did do some terrible things, but eventually the majority of these men will go home; and, would you rather they go home the way they came in, or worse? Or would you rather they learn to change their behaviors, to become productive members of society; people who are going to pay taxes, to raise their children. … They want to work with youth. They want to teach that there is a better way. … I tell the men all the time, ‘You getting a degree does nothing for me; you getting a degree does something for you and your family.’

“Through this program, they form a community in prison that helps one another. And, when they first came into the facility, that was the last thing they’d wanted to do.”

Comments